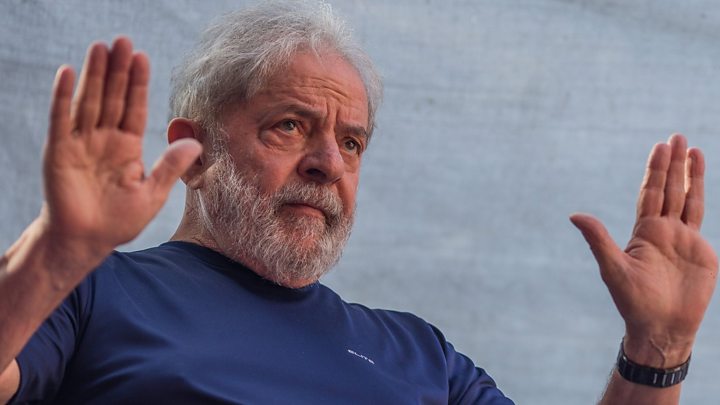

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Lula is lifted by supporters at the steelworkers’ union building in Sao Paulo

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Lula is lifted by supporters at the steelworkers’ union building in Sao Paulo

Brazil’s former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s surrender on Saturday capped a dramatic few days in Brazil. But the political spectacle is likely to continue as the country heads towards presidential elections in October.

“We are going to return to the time where just a few people have a lot of money, and a lot of people have nothing,” Lula supporter Gisele Veloso says.

She was on the verge of tears as she stood outside the steelworkers’ union in the early hours of Thursday morning. It was just after the Supreme Court ruled that Lula had to start serving his 12-year prison sentence for corruption and tensions were running high.

Spectacular fall from grace

For many, Lula still holds a special place. He was Brazil’s first working-class president and helped lift millions out of poverty. He promised change in a country known for its gaping inequalities.

But it has been a stunning fall from grace for a man who was once the most popular leader in Brazilian history. Convicted and jailed for corruption and money laundering, he now has a less flattering claim to fame as the country’s most famous criminal.

Media captionLula forced his way through crowds of his supporters to turn himself in

For millions, including those who had voted for him in the past, he turned out to be just as corrupt as the politicians who came before him. There are now plenty of people who are eager to see him locked up.

Messy months ahead

Even so, it’s unlikely that this is the last we will hear of Lula. Leaders in the Workers’ Party (PT) have already said he remains their candidate for October’s elections.

It is possible for Lula to campaign behind bars – for now. So the next few months will be messy and emotional.

Parties have to put forward names of their preferred candidates by 15 August. The Electoral court then has until mid-September to analyse them.

Lula: Only death will take me off streets A quick guide to Brazil’s scandals

Because of what is known as the “Clean Sheet” law, which was introduced in 2010, anybody with a criminal conviction is banned from public office for eight years. At that point, Lula’s nomination is expected to be thrown out.

But that means for several months, we could have a convicted criminal attempting to be the country’s next leader. This is Brazil and politics is nothing if not complicated – and at times unbelievable.

An act of rejection

For Thiago de Aragão, a partner at political consultancy Arko Advice, this is the end of an era – one that Lula’s Workers’ Party was warned about.

“They knew that this would happen,” he says, adding that they have lined up possible candidates to replace him, including the former mayor of São Paulo, Fernando Haddad.

“From within the Workers’ Party, breaking with Lula is not an option,” he says, adding that Lula has in the past few years become bigger than the party he founded.

“Because of that, a candidate from the party that is not fully endorsed or linked to Lula does not stand a chance,” he adds.

They have a strategy and that, according to Mr de Aragão, is to keep pushing Lula as a candidate until the last moment. When the electoral court throws his candidacy out, that’s when they’ll put forward another candidate.

“They will make this an act of rejection,” he says. “The energy from that moment will then be transmitted to the candidate that will be chosen to run on Lula’s behalf.”

From far-left to far-right

Brazilian politics is increasingly polarised. Trailing behind leftist Lula in the presidential polls is far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro. So could he become number one?

Many experts doubt it.

“The existence of a candidate like Bolsonaro is a product of the existence of Lula,” says Mr de Aragão.

If that’s the case, then it throws the elections wide open. There is a great deal of uncertainty as to the political future of this country. Ask a Brazilian who to vote for and many just shrug their shoulders – they have no idea.

One thing is certain though, Lula’s influence is here to stay.

“He will still be able to do politics even through his silence,” says João Paulo Orsini Martinelli, a criminal lawyer in São Paulo. “His existence will still be there and he’s still a gravitational force within Brazilian politics. He’s a player.”

Additional reporting by Anna Jean Kaiser