Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

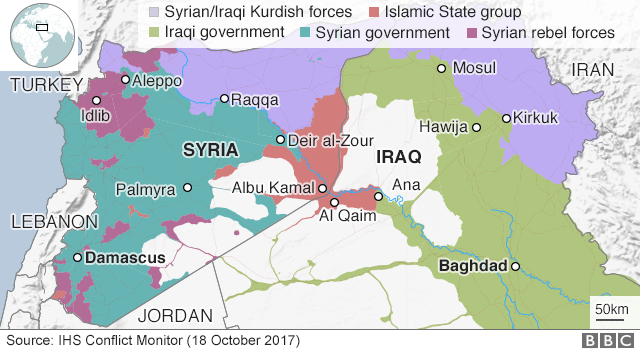

Driven out of their de facto capital of Raqqa after three brutal years, IS fighters have lost much of the territory they once held. How real is the danger they will now travel to other countries to carry out attacks, asks Dr Lorenzo Vidino.

As the self-declared Islamic State steadily crumbles in Iraq and Syria, security officials throughout the world are asking themselves a crucial question: what will happen to its fighters?

Roughly 30,000 foreign fighters joined IS and there is concern that these battle-hardened individuals will return home, or move elsewhere, carrying out terrorist attacks to avenge the demise of the “caliphate”.

While difficult to forecast, the changing fortunes of IS will undoubtedly have major implications for global security.

Over the border

There are indications, including an assessment by US counter-terrorism officials, that some foreign fighters will stay in Syria and Iraq.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

While Turkish authorities have been patrolling with significantly more zeal than in the past, mountainous terrain and the presence of sophisticated smuggling networks mean the border is quite permeable.

IS has a long-established support network throughout Turkey, which is playing a key role in extracting foreign fighters from Syria.

Given the scores of attacks that have bloodied the country over the last three years, Turkish authorities are understandably concerned about this influx.

Neighbouring countries, such as Jordan and Lebanon, have similar fears.

From battlefield to battlefield

The potential end destinations for foreign fighters leaving Syria and Iraq are plentiful.

There is evidence that some have joined the official wilayat, or “provinces”, IS has established in Yemen, the Sinai Peninsula, the North Caucasus and East Asia.

The group also has a strong presence in Libya, where the US suggested last year that it had up to 6,500 fighters, and several hundred in Afghanistan, where the US reported killing at least 94 fighters in an attack on underground tunnels.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Marawi in the Philippines has been partly held by fighters linked to IS since May

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Marawi in the Philippines has been partly held by fighters linked to IS since May

There are also anecdotal indications of militants travelling to conflicts in far flung places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar and the Philippines.

The arrival of foreign fighters to these regions could strengthen the capabilities of local jihadist groups and change the course of sometimes devastating conflicts.

Vulnerable countries

Many other foreign fighters are choosing to return to their countries of origin.

While some returnees may no longer engage in militant activities, others are establishing clandestine networks seeking to carry out attacks and, according to local circumstances, destabilise the country’s political situation.

North African countries are particularly vulnerable to the risk – nowhere more so than Tunisia, as about 6,000 of its citizens left to join IS – the highest per capita rate in the world.

Arab Gulf countries may also suffer from this type of blowback.

Russia, the Caucasus, and a number of Central Asian countries are also areas of concern, having seen large numbers join IS – many of whom went on to play a prominent role on the battlefield.

The threat to Europe

European authorities consider the return of some of the estimated 6,000 European foreign fighters a major security concern.

To date, fewer than one in five individuals involved in attacks on the West since the “caliphate” was declared in 2014 had experience as foreign fighters, according to research by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) and the George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption The Paris attacks were carried out in part by former foreign fighters Who was behind the jihadist attacks on the West? Who are Britain’s jihadists? The archaeological treasures IS failed to destroy

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption The Paris attacks were carried out in part by former foreign fighters Who was behind the jihadist attacks on the West? Who are Britain’s jihadists? The archaeological treasures IS failed to destroy

But this might change as the number of returnees – now estimated at roughly 1,000 – increases.

Many may show no sign of wishing to engage in further violent activities, but there is a valid concern that some may make use of their combat skills.

It is plausible that they could use their network of contacts and “celebrity status” among unaffiliated jihad enthusiasts to plan terrorist attacks.

The territorial losses suffered by IS are not likely to affect the operational ability of these largely independent militants.

A legal return

While significant problems still exist, European authorities have improved intelligence sharing to better detect returning fighters.

And thanks to improved co-operation with Turkey, many militants have been arrested before they get any further.

A few do manage to reach Europe illegally, or by posing as refugees – as some of the November 2015 Paris attackers did.

But most foreign fighters will come to Europe legally, often using their genuine European passports.

If detecting them is a problem, working out what to do with them is equally fraught.

Arresting them may be the obvious answer, but the reality is significantly more complicated.

The UK Home Office, for example, disclosed last year that of the 400 British foreign fighters who had returned from Syria and Iraq, only 54 were convicted.

Similar dynamics can be observed throughout the continent.

Inside Raqqa after IS pushed out The city fit for no one Raqqa’s loss seals rapid rise and fall

Inside Raqqa after IS pushed out The city fit for no one Raqqa’s loss seals rapid rise and fall

What is preventing authorities from arresting, prosecuting and convicting returning foreign fighters?

It is mostly a legal matter, with lawmakers struggling to keep up with a constantly shifting threat environment.

While legislations vary from country to country, they share some common problems.

In some countries, joining a terrorist organisation or fighting in a foreign conflict were not criminal offences at the time when most individuals travelled to Syria.

Several countries have since introduced new laws which, however, cannot be applied retrospectively.

Even in countries where such actions have long constituted criminal offences, authorities struggle to gather the evidence needed to build a strong criminal case.

Knowing that somebody joined IS or committed atrocities in Syria from an intelligence perspective is one thing.

Being able to prove that beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law is another.

Even more complicated is the issue of children either born or raised in the “caliphate” by their foreign fighter parents.

While most are not punishable under the law, they deserve attention because of the trauma they have suffered and, in some cases, because they present severe signs of radicalism despite their young age.

The result is that authorities are overwhelmed, having to monitor hundreds of battle-hardened fighters, on top of the burgeoning number of home-grown IS sympathisers, in an attempt to determine which pose an immediate security threat.

Instead, authorities throughout Europe have increasingly invested in programmes seeking to deradicalise returning foreign fighters.

While it might be premature to definitively assess them, there are indications that some, like the one established in the Danish city of Aarhus – offering rehabilitation and inclusion in society, are effective.

Others, like the French plan to set up 12 deradicalisation centres, have been shelved.

Looking to the future

The loss of much of its territory is a major blow to ISIS.

Yet the group and its adherents are already surfacing in various parts of the world and are likely to do so with even more frequency and vehemence in the near future.

IS will become a more decentralised, amorphous organisation operating in a more asymmetric fashion, but it will not disappear.

Moreover, the IS brand and the emotional appeal of its “caliphate” are unlikely to vanish any time soon.

And, despite critical challenges, the organisation’s remarkably strong digital presence, the so-called “virtual caliphate”, will survive in some form, potentially rekindling the commitment of sympathisers worldwide and prompting some to carry out terrorist attacks in its name.

The fall of the “caliphate” closes a chapter, but a new one is about to be opened.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Lorenzo Vidino is the director of the Program on Extremism at the George Washington University and of the Program on Radicalisation and International Terrorism at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) in Milan.

Edited by Duncan Walker