Image copyright Colin McPherson

Image copyright Colin McPherson

It Is universally agreed that Sir Vidia Naipaul used to be an excellent author of the English sentence; a grasp stylist and story-teller with a chilly, transparent eye for the ironies, tragedies and sufferings of mankind. However here all settlement stops.

For his many supporters, his fiction had cruel comedian clarity and his travel writing a terrifying honesty – refusing to glamorise or idealise the creating international.

They hailed him as a towering mind – handing over an authentic, scorching critique refreshingly devoid of political correctness: attacking the cruelty of Islam, the corruption of Africa and the self-inflicted distress he witnessed in the poorest portions of the globe.

For his a large number of critics, Naipaul’s writing used to be troubling and even bigoted. They recognised his literary gifts but noticed him as a hater: an Uncle Tom who dealt in stereotypes, paraded his prejudices and bathed in loathing for the sector from which he came.

Certainly, he gave lead to for his or her criticism. “There more than likely has been no imperialism like that of Islam and the Arabs”, he as soon as declared. He used to be scornful of the Caribbean, wrote that Africa might revert to the ‘bush’ and often veered against unapologetic misogyny.

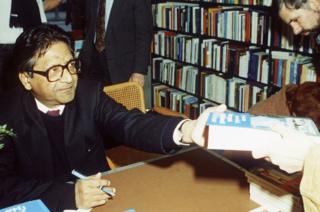

Symbol copyright John Minihan Image caption VS Naipaul in the 1960s – the last decade in which he printed a chain of books exploring his memories of youth within the Caribbean

Symbol copyright John Minihan Image caption VS Naipaul in the 1960s – the last decade in which he printed a chain of books exploring his memories of youth within the Caribbean

His fellow Nobel Prize winner, Derek Walcott, was once scathing. Naipaul wrote beautiful prose, he said, “scarred by means of scrofula” and “a repulsion in opposition to Negroes… a bodily and historic abhorrence that, like every prejudice, disfigures the observer”.

The Instructional, Edward Stated, bridled at the assaults on Islam – announcing he discovered it exhausting to believe any rational individual could attack complete cultures on this sort of scale.

In individual, Sir Vidia may well be affable. But, simply as often, he was as haughty, irascible and quickly provoked to bile. He loved epic feuds with family member and foe, acted unspeakably to girls and gloried in a normal lack of sensitivity to all who crossed his path.

When Salman Rushdie went into hiding after The Satanic Verses, as an example, Naipaul defined the fatwa as “an extreme form of literary complaint.” Then he threw again his head and laughed.

Trinidad

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul used to be born in rural Trinidad on 17 August 1932. The island of his start used to be an advanced post-colonial patchwork of racial tensions and subtle hierarchies.

His grandparents have been labourers: a part of the nice 19th-century Indian diaspora who had settled within the Caribbean. The younger Vidia was raised as a Hindu, part of a displaced community within a plantation society. It was a mix of histories, customs and ethnic identities which later formed the most important part of his paintings.

Naipaul’s father, Seepersad, was a journalist for the Trinidad Mum Or Dad who revered Shakespeare and Dickens. He may read the great works of Eu literature aloud to his children – giving the young Vidia an burning ambition for writing, a “delusion of nobility” and a “panic about failing.”.

He attended the Queen’s Royal College, proving himself an in a position scholar. On graduating, he received a central authority scholarship giving him entry to the Commonwealth school of his choosing. In 1950, he arrived in Oxford.

Symbol copyright Meager Symbol caption Naipaul suffered from loneliness and despair all over his time at University College, Oxford. He found it not up to intellectually stimulating.

Symbol copyright Meager Symbol caption Naipaul suffered from loneliness and despair all over his time at University College, Oxford. He found it not up to intellectually stimulating.

Depression

School Faculty was once a time of poverty and poor loneliness. Isolated and unsure of his long term, Naipaul turned into significantly depressed. On an impulse, he took a visit to Spain the place he quickly ran out of money. there has been a pissed off suicide attempt when the gas meter ran out.

His saviour was once his father, with whom he saved involved by letter: a correspondence Naipaul later published as Letters Among a Father and a Son (1999).

He harboured little affection for his place of birth, describing Trinidad as an “unimportant, uncreative, cynical… dot on the map”. But nor did he warm to Britain either, discovering it a second-charge usa of “bum politicians, scruffy writers and crooked aristocrats.”

He moved to London with his new spouse, Patricia Hale – who he had met at college. His father died and Naipaul discovered himself in yet another small, isolated world – this time as an aspiring writer. “I turned into my flat, my desk, my name.”

With a rising emotional and physical detachment, he began to write about his youth. His first three books – The Mystic Masseur (1957), The Suffrage of Elvira (1958) and Miguel Side Road (1959) – were set within the Caribbean and revealed in quick succession.

To make stronger himself, he churned out guide reviews and made programmes for the radio. “i used to be,” he said, “an accomplished hack.”

Image copyright RUTH POLLACK Image caption Naipaul printed his first three books in rapid succession. Alternatively, his masterpiece – A House For Mr Biswas – took him three years to write.

Image copyright RUTH POLLACK Image caption Naipaul printed his first three books in rapid succession. Alternatively, his masterpiece – A House For Mr Biswas – took him three years to write.

Masterpiece

Then got here his undoubted masterpiece. A Home for Mr Biswas took more than 3 years to write down and, by way of the time final touch, he knew a lot of it by means of center. However beneath the masterful comedian writing lay such a series of uncooked feelings, he slightly ever looked at it once more.

It was a sprawling, Dickensian family chronicle about one guy’s dreams of independence. Mr Biswas used to be from Trinidad, regularly striving for elusive luck. He marries into an overbearing circle of relatives however, without a area, cannot be the author of his own future.

He struggles to build it; putting off his decaying members of the family, growing his freedom and organising self-recognize. specially, it was the writer’s attempt to come to phrases together with his own identification and the pivotal determine in his life: his father.

Biswas represented Seepersad while the character’s son, Anand, stood for himself. About their relationship, Naipaul wrote barely disguised self-research within the form of fiction – with sharp sentences and a merciless pen:

“Despite The Fact That nobody known his strength, Anand used to be among the strong. His satirical feel saved him aloof. in the beginning this was once just a pose, an imitation of his father. However satire led to contempt… It ended in inadequacies, to self-awareness and a lasting loneliness. but it surely made him unassailable.”

The e-book used to be a sensation, revealed to world acclaim in 1961. But Naipaul felt exhausted and done, for now, with writing literature. He spent the next few years traveling within the Caribbean, India and Africa – describing what he saw and achieving for a better understanding of his own, displaced identity.

Symbol copyright BIJU BORO Symbol caption Naipaul had little time for idealistic westerners who romanticised India and looked to it for non secular enlightenment

Symbol copyright BIJU BORO Symbol caption Naipaul had little time for idealistic westerners who romanticised India and looked to it for non secular enlightenment

International traveller

His writings be offering a private perception of history as a series of tragic and haphazard upheavals, leaving “part-made” creating worlds in their wake. An Area of Darkness (1964) chronicles India. Naipaul has most effective contempt for westerners seeking to the sub-continent for a non secular awakening.

Instead, he noticed best ugliness and a boastful refusal to understand the horror of the “slender, damaged lanes with inexperienced slime in the gutters, the chocked back-to-again homes, the jumble of grime and meals and animals and those, the baby in the mud, swollen-bellied, black with flies, but dressed in its excellent-luck amulet”.

In Africa, he took up a creator-in-residence fellowship at a college in Uganda – writing The Mimic Men (1967): a singular charting the struggles of Ranjit ‘Ralph’ Singh to balance his non-public lifestyles and political ambition. Combining components of each fiction and non-fiction, it satirised, because the name suggests, West Indian efforts to imitate the behaviour in their former Eu masters.

He travelled widely about the continent, steadily depicting its lifestyles as bleak and its people primitive. In A Unfastened State (1971) won the Booker Prize with its portrayal of a violent, submit-colonial continent attracting younger, idealistic whites in seek of sexual freedom.

a young American, Paul Theroux, frequently joined him on his journeys. Years later, Theroux discovered a ebook he had given Naipaul in a 2nd-hand bookstall. Angry, he published Sir Vidia’s Shadow, a e-book depicting his former loved one as “a grouch, a skinflint, tantrum-vulnerable, with race at the brain”. the outcome was once an epically bitter 15-year feud.

Image copyright Ira Wyman Symbol caption The American go back and forth author and novelist, Paul Theroux, printed a caustic memoir of his lengthy friendship with Naipaul. ‘Sir Vidia’s Shadow’ led to a fifteen-yr feud between the two males.

Image copyright Ira Wyman Symbol caption The American go back and forth author and novelist, Paul Theroux, printed a caustic memoir of his lengthy friendship with Naipaul. ‘Sir Vidia’s Shadow’ led to a fifteen-yr feud between the two males.

Naipaul’s career noticed bursts of shocking creativity laced with lengthy sessions of author’s block. Highlights incorporated The Lack Of Eldorado (1969), Guerillas (1975) and A Bend In The River (1979) – an image of submit-colonial Africa spiralling into hell.

Its first line captures Naipaul’s trust that the arena is what man makes it; accountability for its failings unattainable to escape: “the world is what it’s”, he wrote. “Men who’re not anything, who allow themselves to turn into not anything, don’t have any position it it.”

He swung his gaze on Islamic fundamentalism within the Believers (1981). One Big Apple Times creator observed that it bore an antipathy to the faith so bare “that a e book taking a comparable view of Christianity or Judaism would have been exhausting put to seek out a writer” in The United States.

Image copyright Gerry Penny/EPA/REX/Shutterstock Symbol caption Sir Vidia Naipaul gained the Nobel Prize for literature in 2001. Sir Paul Nurse, the winner of that yr’s Nobel Prize for medication, congratulates him.

Image copyright Gerry Penny/EPA/REX/Shutterstock Symbol caption Sir Vidia Naipaul gained the Nobel Prize for literature in 2001. Sir Paul Nurse, the winner of that yr’s Nobel Prize for medication, congratulates him.

In his later years, he entered an autumnal section with The Enigma of Arrival (1987) and Some Way within the World (1994), combining personal revel in (despite the fact that denying it used to be autobiographical) with the wide historic sweep of submit-battle migration from growing world.

Nobel Prize

A knighthood adopted. And In 2001, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. The Academy compared him to Joseph Conrad and extolled his talent to “turn into rage into precision.”

He rarely gave interviews, loathing newshounds. at the rare instance he did, he forever proved great replica: gaily describing Tony Blair as a “pirate” whose “socialist revolution” created a “plebeian tradition”, brushing aside Dickens as a author who died of “self parody” and skewering EM Forster as a person who knew not anything about India “but the garden boys whom he needed to seduce.”

Sir Vidia Naipaul will likely be remembered as a paranormal craftsman of English prose. He additionally believed the unconventional is “useless”.

He leaves in the back of a complex, challenging library of work which – despairing of the restrictions of fiction to describe reality – occupies an area between creativeness, commute-writing and autobiography in his attempt to seize the complexities of the modern international.

He noticed himself as a lone, stateless observer; free of ideology, politics and phantasm. To his champions, he had few equals.

For the Turkish creator Orhan Pamuk, Naipaul represented third-international other folks “not with sugary magic realism however with their demons, their misdeeds and horrors – which made them less victims and more human.”

But to his detractors, Naipaul was once necessarily political; bearing witness towards the post-colonial global with great writing but protected from criticism through virtue of being ‘one of them’.