China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road initiative has taken Central Asia and Africa by storm, but the European Union and its prized purchasing power may be Beijing’s real endgame.

WARSAW, Poland — China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road initiative has taken Central Asia and Africa by storm as developing countries line up for Beijing’s money to break ground on pricey, China-backed and China-financed infrastructure projects.

But some analysts say the European Union and its prized single market, the second-largest economy in the world in terms of purchasing power, is Beijing’s real endgame.

As Beijing courts Eastern and Central European states in order to better access lucrative Western European markets, the European Union’s leading powers — France and Germany — are concerned that Chinese investment in the bloc’s newer and less-prosperous states will increase Beijing’s influence in the region and only widen the ideological rift between the eastern and western halves of the Continent.

Hungary and Poland, already feuding with EU leaders in Brussels on such hot-button issues as immigration and civil liberties, may be drawn to China’s far less judgmental approach to investment and development.

China’s Eastern European ambitions even have a bureaucratic base — the 16+1 Group linking China with 16 countries along Europe’s eastern flank from the Baltics to the Balkans. It includes 11 countries that are also members of the EU.

Viktor Orban, the nationalist Hungarian prime minister who has feuded repeatedly with the EU’s western powers, hosted the 16+1 annual summit in Budapest in November. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, Chinese companies backed by government banks have announced plans for $15 billion in roads, railways, utility plants and other infrastructure since 2012 in the 16 countries.

While many of the governments involved insist they are not seeking a break with the EU or the West, Mr. Orban recently told reporters that “the world’s economic center of gravity is shifting from west to east. While there is some denial of this in the Western world, that denial does not seem to be reasonable.”

Stefan Meister, who heads the Robert Bosch Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia at the German Council for Foreign Relations in Berlin, said in an interview that “the main aim [for China] is not Central or Eastern Europe, but its completing the Belt and Road infrastructure via these countries.”

“The side effect is that you can use all of the weak spots to block other decisions which are linked to China,” he said.

Others say the fear is overblown. Despite the worried analyses of the past five years, Chinese direct investment in infrastructure — particularly in the region’s EU and NATO states — has been negligible. Despite the grandiose promises and ballyhooed rollouts, many of the most ambitious projects have yet to break ground.

But the possibility of a continental divide spurred by the lure of easy Chinese financing has clearly caught the attention of the EU’s traditional powers.

German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel warned in a speech in September, “If we do not succeed in developing a single strategy towards China, then China will succeed in dividing Europe.”

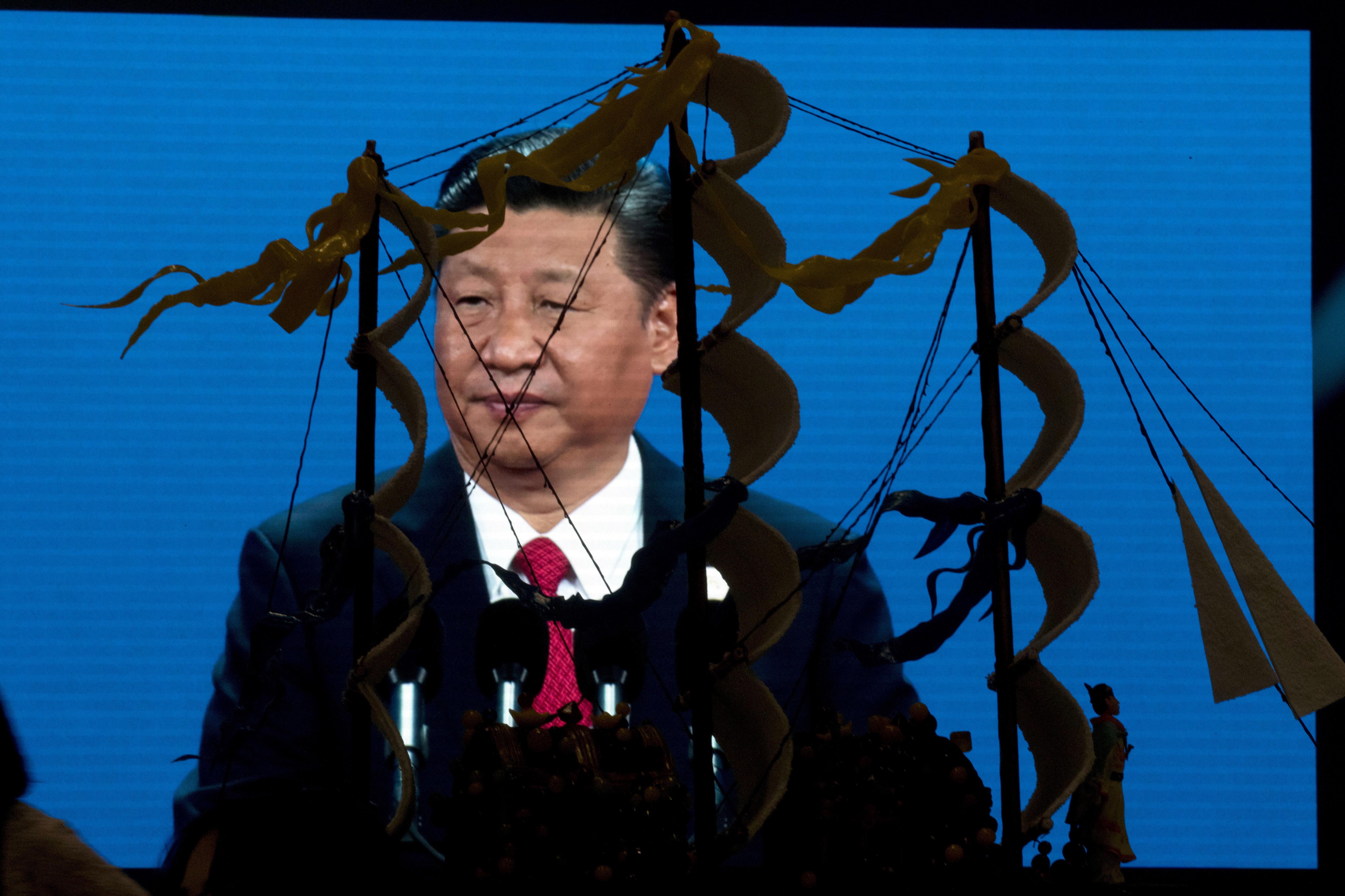

Launched in 2013 under increasingly powerful President Xi Jinping, China’s Belt and Road initiative has sought to develop modern transportation links throughout 64 countries, coming into contact with 60 percent of the world’s population and a third of its economy along the way.

The project is the centerpiece of a multipronged effort by Mr. Xi to use China’s soaring economic clout as a means to reshape the global financial and political balance of power.

China’s vast government currency reserve that can be used to underwrite overseas investments has been a prime engine of Beijing’s drive for greater prominence, giving it influence and leverage in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Last year alone, China put $81 billion into Europe in foreign direct investments, up 76 percent from 2016, according to a report by law firm Baker McKenzie.

Britain, the Netherlands and Switzerland received the most Chinese capital last year, but some $9 billion has flowed through the EU’s eastern and central states as part of the Belt and Road initiative. Last year, China established an $11 billion investment fund for the region and promised an additional $3 billion at the November summit in Budapest.

Projects underway

The fruits of Chinese largesse in the region aren’t quite as visible as elsewhere in the world, but notable projects have already drawn attention.

Seen as the “dragon head” of its Belt and Road initiative in Europe, China’s state-owned shipping firm, the China Ocean Shipping Co., agreed in 2016 to invest some $1.24 billion into Piraeus, Greece’s largest port. At the time of the announcement, the firm bought a 67 percent stake in Piraeus for $457.5 million and pledged $620.9 million to modernize shipping facilities over the course of time, according to reports.

With Piraeus as China’s gateway to the Continent, goods will be shipped through Central and Eastern Europe via a proposed high-speed railway between Belgrade, Serbia, and Budapest, Hungary, estimated to cost $3.8 billion. Construction on the project broke ground in Belgrade in November thanks to a $297.6 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China.

Construction on the Hungarian portion expected to start in 2020. Ex-Im is providing 85 percent of the credit needed to fund the project.

Such projects have been welcomed by Eastern and Central European states, where the infrastructure gap with the European Union’s western members is expansive and the EU hasn’t acted fast enough to bridge the divide, said Angela Stanzel, a policy fellow in the Asia and China program with the European Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin.

Poland and Hungary in particular are hungry for investment and opportunity alternatives, officials say.

“We are ready to be the gate to the West, first of all, from the economic viewpoint. This also includes China’s One Belt, One Road initiative,” Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said in October during an economic cooperation summit in Belarus, when he was Poland’s minister of economic development and finance. “Here, we can develop mutually beneficial cooperation for our countries and nations.”

Even in countries like Romania, where Chinese investment has yet to be felt in a major way because of weak diplomacy and economic policy, links between former communist states and China can be exploited for both countries’ benefit, said Aurelian Dochia, a Romanian economist.

“Romania didn’t make enough efforts and did not find the best way to convince the Chinese that their presence in Romania would be interesting,” he said. “I think it shows a weakness in Romania’s diplomacy and economic policy.”

Even so, Romanians have been wary of the Chinese. As prime minister, Victor Ponta was heavily criticized in 2014 for a visit to China in an attempt to move closer to Beijing instead of focusing solely on Western Europe.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s growing investments in the region have put pressure on recipients to get in line with Chinese policy initiatives, said Ms. Stanzel, even though Brussels has managed to patch things up within the bloc on most economic and sociopolitical issues involving China.

“On the sensitive issues, the member states are already divided,” said Ms. Stanzel, noting that Greece and Hungary objected to strong language from the EU condemning China’s island-building and aggressive sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, and that a veto by Hungary last year stymied a common EU statement on China’s human rights abuses.

“Now it seems as if there are very few countries, such as Germany and France, that keep sticking to mentioning the sensitive issues such as human rights, whereas all the others just don’t do that anymore,” she said.

Challenging the EU

Hungary and Greece, recipients of Belt and Road cash, have long been at odds with dominant powers within the EU: Greece for the austerity programs it was forced to adopt during its long, costly economic crisis, and Hungary for the country’s rightward, anti-immigrant swing under Mr. Orban. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic and Poland, strong European economies and benefactors of lucrative Chinese trade deals, have elected more nationalist, conservative leaders.

These countries are using Chinese investments to say that “they’re sovereign states, that they have alternatives [to the EU],” said Mr. Meister. “In this way, it plays more into this narrative that these are problematic countries, that these are troublemakers, and now they’re even doing deals with China and even voting for China inside of the EU.”

Jakub Jakobowski with the Center of Eastern Studies at the University of Warsaw, however, argued that it is the Western European member states that should rethink their attitudes toward China and Chinese foreign direct investment.

“In Western Europe, they say big Chinese investment appeared in Eastern Europe and this makes the region more dependent on China, but this is not true,” he said. “Maybe this opinion stemmed from the fact they expected bigger capital to come to their region.

“Presence of Chinese capital in the region … is even smaller, as we receive only a fraction of the investment which comes to France or Germany, for example,” Mr. Jakobowski said.

Germany and France are huge recipients of Chinese investment, and their respective leaders have made numerous personal visits to China to attract business. Even so, both countries have remained steadfast in condemning what they say are unsavory global and domestic policies out of Beijing.

“Mutual dependencies are increasing, and sometimes the balance of power shifts,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel told German weekly WirtschaftsWoche. “Europe must work hard to defend its influence, and above all it should speak with one voice to China.”

But China’s push in Eastern Europe threatens to upset Franco-German economic and political dominance in the bloc at a time of heightened instability on the Continent, said Mr. Meister.

“Germany is only very slowly understanding what is going on here and, at the same time, China is so important as a market also now for Germany that we have no interest in a huge conflict with the Chinese,” he said.

But EU champions can’t afford to dawdle on the issue, Mr. Meister added.

“This is about the future of Europe,” he said. “This is the future of our industries, our technology, and we’re already really too late. The Chinese are already in many areas.”

⦁ Austin Davis reported from Berlin. Vlad Odobescu contributed reporting from Bucharest.